- Photo Number:

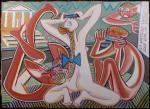

- 01122

- Size:

- 35" x 25.25"

- Category:

- Paintings

- Artist:

- Mazur, Zygmunt

- Medium:

- oil painting

- Description:

- "La comtesse tarnowska jue sur un peigne" - a recurring theme, that of the sexual awakening of youth, is exhibited by this piece - by Expressionist artist Zygmunt Mazur (Poland, Lebanon, North America 1922-2001)Zygmunt Mazur was born in Wodzinow, Poland on January 1, 1922. In 1940 his family was taken to Siberia. In 1942 Zygmunt was called from Sibaria to join the Polish army in the Middle East. He began his formal training at the Académie Libanaise des Beaux-Arts in Beirut, Lebanon, shortly after WWII. Mazur’s professional artistic pursuits spanned almost six decades, lasting from approximately 1945 to 2001, during which time he explored and produced pieces in various media ranging from printmaking and sculpture to tapestry, all proving popular enough to provide him a comfortable income.Yet after the 1970s he apparently made virtually no attempts to sell or even show his astonishingly creative paintings and drawings. Mazur's notes reveal that he did not wish for the public to know his works while he lived for fear of losing his privacy. He cared not for money and rejected fame.Fortunately, a cache (many hundreds of pieces, all quite unique and, though nearly all unsigned, readily recognizable as his work) was bequeathed after his death to a young couple who had been his next-door neighbors at the end of his life. This cache was consigned to an auction house in Albany, New York, with the bulk eventually acquired in 2004 by a major art gallery/dealer on Madison Avenue in New York City, which sold them all within less than a year.In Beirut, Lebanon, the Academy of Fine Arts was founded in 1937, organized by Polish exiles after the War, and employed Lebanese, French, and Italian instructors. As a result, Mazur and his Polish, Arab, and European contemporaries were exposed to classic techniques as well as international art movements such as Fauvism, Expressionism, Symbolism, Cubism, and Surrealism. This influence is apparent in many of Mazur’s works, which stylistically reference artists like Matisse, Nolde, Heckel, and Picasso. During his time at the academy (c.1945-1949), two major exhibitions that coincided with larger international events in Lebanon were generating an atmosphere of cultural acceptance and artistic freedom. These were the Dhour Shoueir exhibition (1947), opening just prior to the inaugural Arab cultural congress held in Beit Mery, and the UNESCO exhibition (1949), organized to celebrate the UNESCO congress being held in Beirut that same year.Mazur and artists like him such as the Basbous brothers, Chafic Abboud, Farid Awad, Paul Guiragossian, and Stanislaw Frenkiel contributed to the many exhibitions held in Beirut that highlighted professional and amateur artists alike who were active in the cultural community surrounding the Academy.For example, in 1947, Mazur had a number of works in the exhibition, L’exposition des Jeunes Peintres Polonais au Liban, organized by the Polska YMCA located in the Université Américaine à Beyrouth. And again in 1948, he had several pieces in an exhibition organized at the Musée National de Beyrouth entitled Exposition des Peintres Polonais de Beyrouth. While a student at the Academy in Beirut, Lebanon, Mazur married Maria Strawinska, also a painter, as well as a lawyer and teacher. Strawinska began studies in Krakow, Poland and continued in Beirut.Mazur immigrated to Canada in August 1949, and became a Canadian citizen on June 5, 1955. Strawinska accompanied Mazur to Canada where they lived together until her death in 1992.Mazur was asked to contribute two pieces to the 1950 show, Exposition des Artistes Polonais en Exil Etablis au Canada, organized by the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Montreal. At the time of his immigration to Canada in 1949, Mazur’s work had already evolved into a unique, highly stylized brand of Expressionism. This evolution continued to develop through the 1950s and 1960s, and although Mazur experimented with subject matter and types of media to create visions of a subjugated reality, he stayed true to the stylistic tenets of the German Expressionism he was exposed to as a student in Lebanon. Therefore, his works during these years are consistently marked by elements of intense psychological introspection, bold abstract colors, and flat distorted figures. These pieces were popular with Mazur’s growing audience. He had almost perpetual commissions for metalwork (Toronto, London, Australia, New Zealand, and Bahamas), and occasionally accepted but often rejected commissions for painting and illustrations.By the 1970s, Mazur embarked on an artistic journey that took the formal aspects of his art much closer to that of Neo-Expressionism infusing both European and North American stylistic trends. This Post Modern movement is characterized by violently distorted forms and intense use of color. As a result, his later works often display neon colors used in much of the graphic and pop art designs that became popular at this time. His subject matter often represents the artist’s own cultural mythology and an ahistorical ambiguity that represents an underlying tension resting, at times, just on the edge of violence. As a result, even though Mazur continued to explore themes and ideas that informed his early works, his later works depict distorted human forms that are infused with sexuality and display an overtly inner turmoil that play out scenes of frustrated, almost alienated erotic mythology tension based on “primitivizing themes.” Such themes are readily evident in Mazur’s tapestries, a medium that was central to his artistic production toward the late 1980s. The challenge of both designing and weaving his own tapestries forced Mazur to call on his formal artistic training and his technical drafting skills, honed during his postwar training as a technical engineer. Concerned with “a craftsman’s posture at the loom” and unsatisfied with his commercial options, Mazur designed his own loom that allowed him to weave on a slanted surface, the way medieval scribes sat to illuminate their manuscripts, rather than weaving strictly on a horizontal or vertical surface. With the same determination that he approached his loom design, Mazur tackled the process of weaving: He studied the ancient art form of tapestry weaving from books describing the intricate and complex method of setting the warp, manipulating the weft, and executing the design. It was the challenge of working with this medium that consumed Mazur until his death in Laval Des Rapides, Quebec near Montreal, in 2001. (Item 01122)

If you are interested in buying this item if it ever becomes available for sale, or interested in selling a similar item, please click here!